A personal narrative in time(s) of emergency: Part One

Canterbury Anniversary Day, AMP Show, 2004.

By Tim J. Veling

The following text comprises part one of a two-part feature.

Originally drafted in response to the Curating Under Pressure conference held at the University of Canterbury in 2015, the first draft found its way – quite randomly and without opportunity for me edit and elaborate on certain vague statements – into an e-book publication. At the time, rather than ask to have the draft removed from circulation, I thought it best to keep it online. I felt it better to be part of the main conversation, in whatever form, than to self-isolate on its fringes. (Excuse the pun…)

Living through the current Covid-19 lockdown, I am reminded of all the things I felt while negotiating the immediate aftermath of the 2011 Christchurch earthquakes. Living through this state of national emergency has prompted me to revisit this text and attempt that final, or at least better realised edit. It has also given me the opportunity to use illustrations.

My voice within this expanded piece of writing was undoubtedly influenced by my state of mind during this time of social-distancing, family ‘bubbles’ and, frankly, heightened sense of paranoia. I am also aware that while attempting to better qualify some things within the original text, I have gone down a few rabbit holes and not quite been able to find my way out – I have made more vague statements in need of qualification and yet further thought. And so it goes…

It is my intention to post more features in the coming months that, in roundabout ways, supplement this text by meditating on aspects of my own practice, motivations and influences. Put simply, on a personal level this seems like a productive thing to do while forced to be on lockdown.

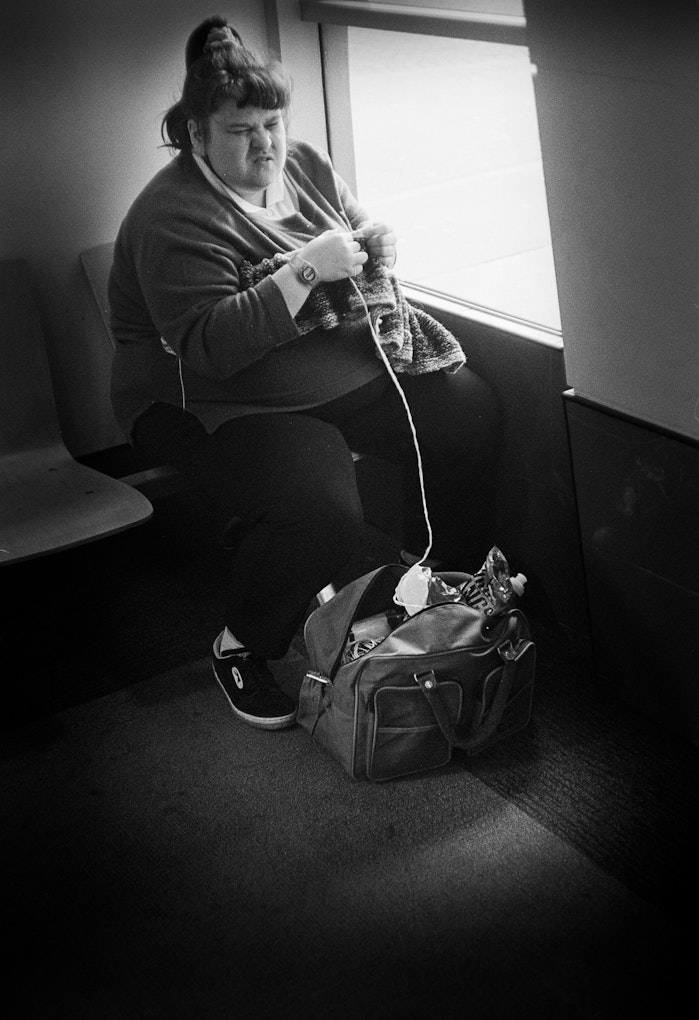

Christcurch Bus Exchange, 2005.

The house was taken by an almighty jolt. The kitchen cupboards flew open and emptied their contents on the floor. I quickly scrambled and tried – unsuccessfully – to brace myself under the doorway. I could hardly keep my footing, so all but gave up. The street, seen through the kitchen window, undulated like waves. Behind me, the lounge windows buckled before shattering into thousands of glass shards. As quickly as it all began, the world fell silent save for distant car alarms.

After plucking up courage, I scrambled next door to check on our elderly neighbor. She wasn’t home, so I inspected both our houses for obvious signs of structural damage then ventured towards the street. To get there, I had to wade through a foot of liquid filth that had bubbled up through a massive sinkhole in the driveway. An aftershock struck and the concrete slab adjacent to the hole crumbled. I struggled to keep my bearings, finally reorienting myself on the street. By this time, half the neighborhood stood with me.

In the days following the February earthquake, people ran on adrenaline and a kind of lawlessness reigned. The charged environment brought out the best and worst of people. For example, it was suddenly excusable to drive like a maniac; strangely admirable to swear like a trooper in public and sporting to demand large discounts in shops as exhausted people struggled to hold themselves together in the face of frequent aftershocks.

A week after the quake, I witnessed a DVD rental shop attendant being subjected to an aggressive tirade from a customer over the phone. The attendant said he was closing early that evening because his neighbor had died in a central city building. He explained that his wife was terrified and that he, “Needed to tend to more important things.” “I don’t give a shit about any of any of that,” I heard the customer yelling down the line. “Just do your fucking job and let me rent a movie.”

Canterbury Anniversary Day, Lincoln Road, 2004.

Thankfully, this kind of behavior was not the normal for everyone. Amongst a predictably melodramatic core of reporting, perhaps the most positive stories of the post-quake city came in the form of news footage showing members of the Student Volunteer Army working en masse, shoveling liquefaction silt out of peoples’ homes and driveways and checking on the wellbeing of otherwise perfect strangers. When electricity finally returned to our house and we setup our tiny television beside the bed – which we’d wheeled into the living room, away from broken bedroom windows – my wife, Lizzie and I watched stories about people banding together by simply ‘mucking in’ and getting on with the cleanup job at hand. Unfortunately, these stories were out of step with our own experience.

Three days after the quake, I stood in our kitchen thinking about making a coffee. Lizzie and I had been shoveling silt and sewerage from our driveway, moving it one wheelbarrow at a time onto the street for council workers to pick up and dispose of. While I poured boiled water into the coffee plunger, I watched as Lizzie struggled to shovel muck into the wheelbarrow. A hotted up Subaru station wagon full of young men edged up to our property and drew to a halt. Having seen kindness on television, I figured help had arrived. I breathed a sigh of relief and grabbed a few extra mugs. Lizzie obviously thought the same, because she put her shovel down, wiped her forehead and waved at the car. They wound down their windows and without any exchange of words, pointed their iPhone cameras at her. After snapping several pictures they wound their windows back up then drove off. Lizzie swore and stomped inside, tears rolling down her cheeks. The scene hit a real nerve and while something of a stretch of conscience, in that moment I felt ashamed to call myself a photographer. With largely sensationalist media reports dominating the media – the disaster distilled down into footage of distraught people, broken buildings and flooded suburban streets – I wondered what on earth I could achieve; if there was anything remotely constructive I could do or say in the face of such widespread grief and suffering. With so much visual dross clogging up social media, let alone dominating reputable newspapers and national broadcast channels, how could I ever reconcile for myself the act of image taking in this context?

Up until this time I considered myself something of a ‘run and gun’ type photographer. My principle heroes were the classics of what is broadly considered the ‘street photography’ and ‘social-realist’ genres: Robert Frank, William Klein, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka, Helen Levitt, Diane Arbus and W. Eugene Smith, to name a few. Despite my best efforts to emulate and / or assimilate aspects of what I loved most about each of these photographer’s work within my own practice, I never found a happy resolve – it was an inherently imbalanced equation, failing to take into account my very introverted personality and the different social-political and cultural climate I was working in. In hindsight, what I admired most in those works – the fearlessness required to get the shot and / or the often in-your-face confrontational subject matter – was what I thought I had to duplicate in order to overcome inadequacies I perceived within myself, mostly due to limited worldly experience. In short, this meant picking up the camera felt like arming myself for combat. The glove(s) didn’t fit – not by a long shot – and I was acutely aware I couldn’t justify pushing on with this way of working during a time of great stress.

Ilam Road, 2006 and Clyde Road, 2006.

Unable to identify a better way forward for myself, I didn’t pick up my camera for several months. Except for a handful of iPhone snaps of our house to send relatives, I didn’t take a single photograph. This was no small problem. Instead of spending time making work on which the future of my family’s livelihood relied, I’d go for long, solitary walks around the cordons that had been hastily erected around Christchurch’s CBD immediately after the quake. Sans camera, I’d find myself standing at military checkpoints staring at distant buildings trapped in what was known as the Central City Red Zone. I’d think about all the places I’d once regularly frequented but that were suddenly off limits. From all the government reports I understood that when the cordons were eventually removed, the buildings that defined my home city; the places I’d accumulated memories and found a real sense of community within would no longer exist. Then Earthquake Recovery Minister, Gerry Brownlee (good riddance) declared the “Old Dunger” buildings that made up much of the CBD would be forcibly torn down, whether they were critically damaged or otherwise. No questions asked, no room for discussion – reduced to rubble, there’d be no going back.

To rub salt into metaphorical wounds, a company named Alcatraz Temporary Security Fencing had supplied a good portion of the components used to construct the Red Zone cordons. I couldn’t help but cringe every time I saw their logo. The obvious irony here being Alcatraz, the legendary island-prison was designed to keep undesirables, those found guilty of breaking the law ‘inside’. Here, Alcatraz fencing served to lock the public ‘out’ for the supposed good of their own safety, no matter what the specifics of the individuals situation or character. This significant distinction had a profound effect on the wellbeing of Christchurch’s public, who quickly came to feel largely disempowered by all-powerful organizational structures and decision-making processes that defined the recovery.

Colombo Street, 2007 and Lyttelton Fish and Chip Shop, 2006.

During this time I decided to contact Alec Soth, member of the esteemed Magnum Photos agency. I had met Alec when attending a workshop in Auckland several years earlier. I was peering through a stretch of wire-mesh Alcatraz cordon fence and was reminded of something he’d said during a lecture. My recollection was that he’d been asked by a major publication to document the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in areas he’d once photographed as part of his seminal body of work, Sleeping By The Mississippi. His response – again, as best I can recall it – was that he didn’t think it appropriate to return as a relative outsider with his large-format camera and engage in the act of aestheticizing such widespread damage and human suffering.

Despite a large amount of self-conscious reservation, I sent Alec an brief email explaining the circumstances in Christchurch. I outlined my difficulty in identifying a way to move forward with photography – how I wanted to give up – specifically how to acknowledge and respect the very raw and sensitive nature of the situation for people as it was unfolding. His response was short and sweet. In essence he said that unlike him in relation to New Orleans, I call Christchurch home. From what he knew of me, my previous work hinged on exploring what my home and surrounding people meant to me. In a sense, I was a product of the city and if anyone should be attempting to make work about the situation it should be someone with a genuine local connection, work history and love of the place. The trick would be to try and avoid the sensationalist signs of trauma. In other words, I took the task to be ‘show’ not ‘tell’; to challenge people to think around the peripheral instead of confirm hard facts that people already knew to be true. Beyond simple words of encouragement, he said I owed it to myself to at least try and find my own way. This was all the validation I needed.

In response to this and at risk of throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater,

I quickly decided the only way for me to progress was to sell all of my prized, small format Leica cameras and invest in equipment of their antithesis. I bought a hefty tripod and a large format field camera – an unwieldy piece of equipment of the kind I’d never seen in the flesh before, let alone used. To move forward, I made the conscious decision to look and act as conspicuous as possible when on the street; to not ‘run and gun’ and remain aloof as I had with my handheld cameras, but make myself as visible and open in my intentions as possible. I bought a fluorescent orange reflector vest and helmet to wear while I was photographing. Overall – perhaps rather naively – I hoped this dramatic change of working methodology would help separate me from the masses of “rubberneckers” that huddled in front of every dilapidated building and liquefaction sink-hole on every street.

Fendalton Takeaways, 2007.

With new equipment in hand, I set off on my usual well-trodden path around the Red Zone cordons. When I happened upon vantage points from which subtle, telling details seemed to come into alignment – the implication or potential meaning of these details was sensed very much intuitively at this point – I’d stop and set the camera up on its tripod. Avoiding any form of technical trickery, I’d position the camera at eye height then level it perfectly. Attempting to emphasize a kind of physical and mental distance within the image plane, I’d include a large amount of foreground within each composition. I’d use a wide-angle lens and point it straight ahead – a side effect of this type of lens being that it emphasizes the difference in size or distance between foreground and background objects. On the camera’s ground-glass I’d bring structures that lay beyond the cordon fences into sharp focus. While doing this, I’d contemplate the buildings I could see that were rumored or confirmed to be pulled down due to safety concerns, or as a result of Gerry Brownlee’s ‘old dunger’ mandate. I’d do all of this under a dark-cloth, using a magnifying loupe to search for fine architectural details not visible to the naked eye, analyzing every part of the image right out to the extreme edges of the frame.

This slow and methodical process became an exercise in heightened looking; in forcing myself to be present. It necessitated absolute concentration and scrutiny of all actions and decisions leading up to the moment of exposure. In addition to this mental game, while I worked people would stop to talk and ask me what I was doing. Without fail or prompting, they’d share their own post-quake narratives, thoughts and feelings. This was almost always a welcome distraction. While talking to them I’d inevitably expose a few sheets of film then let them look under the dark-cloth. “Everything is upside down and back to front,” they’d tell me. They were of course correct in more ways than one.

+++

Part Two to follow...

From Orientation, 2011. Corner of Armagh and Durham Streets. Facing east.