Interview: Glenn Busch By Tim Veling

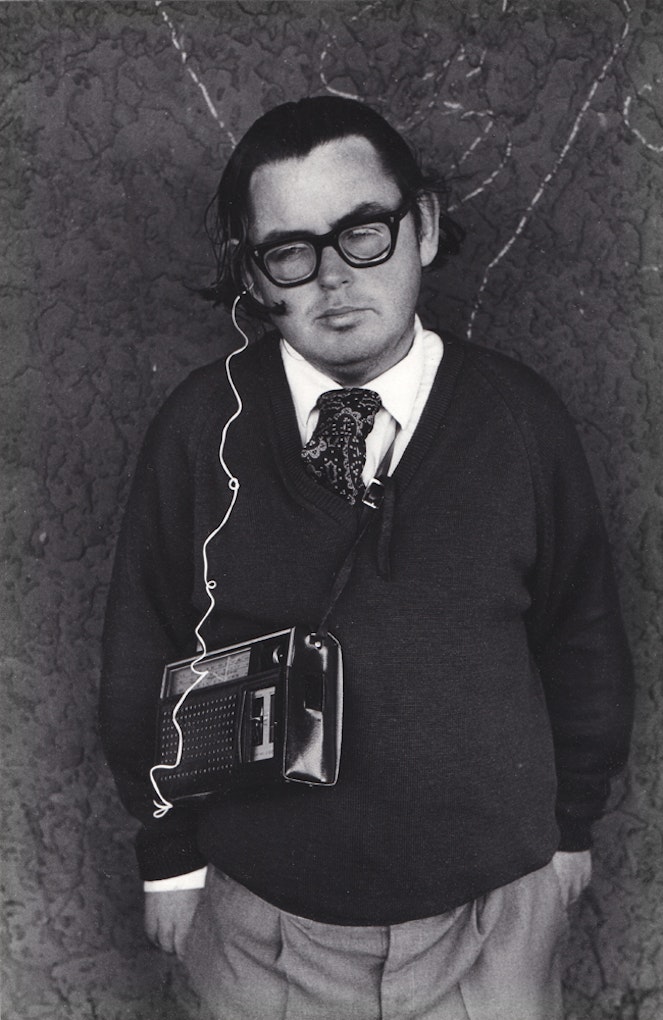

Glenn Busch

Man with a transistor radio

1973

Glenn Busch was initially drawn to photography through its biographical and documentary possibilities. In 1973, he had his first exhibition and founded Auckland’s first contemporary photography gallery. Busch’s photographs, like those of his sometime collaborator Bruce Connew, are firmly entrenched in the social realist tradition of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans.

This interview originally appeared in Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters and Debate in New Zealand, edited by Nina Seja, published by Rim Books in 2014.

TV: So to begin with, can you tell me a little bit about how you got interested in photography?

GB: Well, you might say my education was limited. I left the last of the many schools I attended a couple of months before my fifteenth birthday and I drifted around Australia and New Zealand, working in various jobs, mines, factories, sugar mills, wherever, whenever I had the need for some money. By the time I was twenty-one, I was married, I had one child and another one on the way, and I found myself living in a garage—somebody’s shed in the outer western suburbs of Sydney.

I can remember coming home on my twenty-first birthday and having a little celebration, a cake and bottle of beer.

I can remember coming home on my twenty-first birthday and having a little celebration, a cake and bottle of beer. Then, while the family took themselves off to bed, I sat there a while longer at the table thinking about myself, my life, and what the hell I was going to do with the rest of it. The copper mill I was working in at the time was not a place I wanted to stay in for the rest of my working days. In fact I’d done quite a lot of different things in my life by then, some of which had been enjoyable, even fun, but none of them—except for the birth of my daughter, and later my son—had been what you might call fulfilling. I guess you could say that I wasn’t particularly happy with the way things were and I began to wonder how I might do something more interesting, more worthwhile, with my life.

Not long after that, I went to see a movie called Blow-Up, which was the first English-speaking film by Michelangelo Antonioni, one of the great Italian film maestros. At the time I grasped very little of the social or political implications of the film; what I did find striking was this macho photographer, played in the film by David Hemmings. If I remember correctly the film opens with him photographing in a shelter for old men, making photographs for an “art project” he is working on. To me, at the time, that seemed to be cutting edge documentary—I sort of fell for that one. It’s not what I would think now, but at the time I was totally taken in by it. Certainly from where I stood at that point I suppose it looked a hell of a lot more exciting than working in a factory.

Not long after seeing the movie I saw an ad in the in the Sydney Morning Herald—a photographer advertising classes in photography—and I thought, “Well, why not.” So I went along to this class. It was held in a rather dingy Sydney office space. There were a few chairs scattered around, and two or three large aluminum reflector lamps—flood lamps—on stands, at the front of the room. As we came in the door he took five pounds from each of the eight or nine people that turned up. And then, using his pretty assistant as his model, proceeded to show us how lights shone from different directions created different visual effects. I found it extremely boring and although I told him I would come to his next lesson, I never returned.

I think the second thing I did was go to a camera club meeting one day. They invited me on a field trip out to a beach of petrified wood. I remember them as kind people who did a good line in sandwiches. They were also quite pedantic about how photographs should be made, there seemed to be a lot of written and unwritten rules—the idea that maybe there should be no rules at all seemed an anathema to them. I remember I enjoyed the day. I still have a piece of that petrified wood somewhere I think, but once again I was bored silly.

Some months later, living back in Auckland by then, I found myself passing the Art Gallery and on a whim decided to go in. And it was there by chance and good luck that I walked into a room full of extraordinary people. Easily the most astonishing and exotic mix of individuals I had ever seen before. Artists, sailors, dancing girls, and gangsters, even laborers like myself, in this one room. One in particular really took my fancy, an enigmatic old woman, sitting at a bar, covered in cheap jewelry. Known as Miss Diamonds, the multi-colored baubles that lay all about her were said to mimic an earlier and somewhat different life. In front of her sat a glass of wine, half empty, half full.

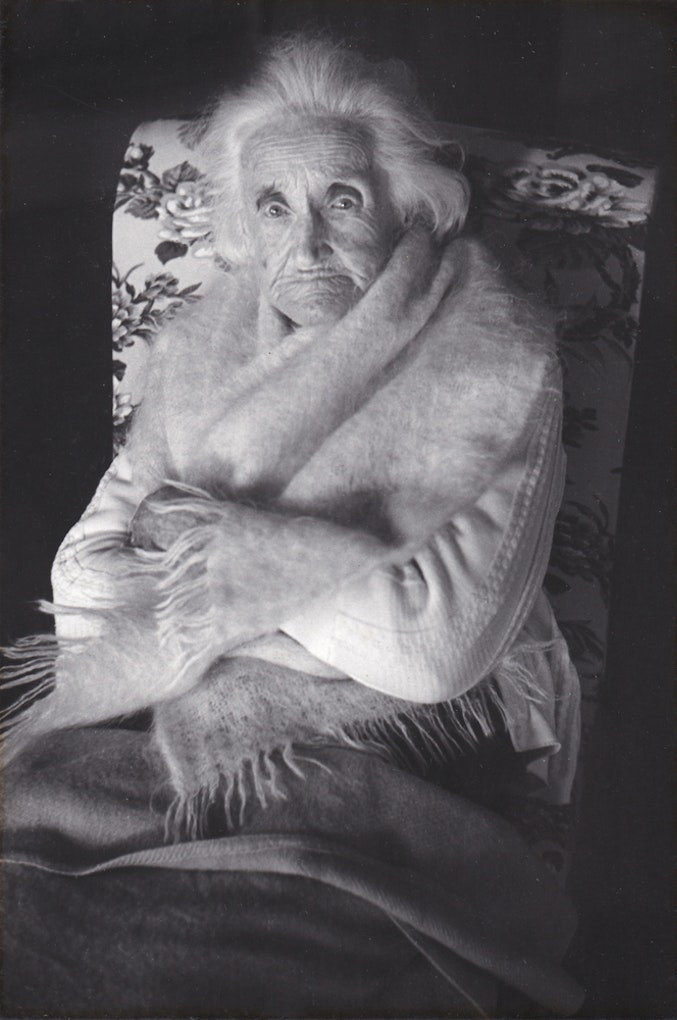

Glenn Busch

Woman at a Retirement Home

1973

GB: The truth is, of course, that the people who filled this room were not actually living human beings, but portraits, superb photographs by the man now known by his pseudonym, Brassaï. To see such work in New Zealand at that time in the 1960s was, to say the least, unusual, and what happened when I saw those photographs was also unusual. I think that was the moment, seeing those pictures, unlike anything I had ever seen before in my life, that’s when I knew what it was I wanted to do. I wanted to try to make pictures that might affect people in the same way that these pictures had affected me. So changing my life that day was as simple as walking into a room. Where within just a very short time my life suddenly seemed to take on some sort of shape and purpose that it hadn’t had before.

After I left the gallery I walked a few hundred yards up the road to the polytech and asked them if they had a photography course. “No,” they said, “I’m sorry we don’t, but you could try further up the road at the university.” So I did that. I walked up to the university, to Elam Art School and I talked to a secretary there, the woman on the desk. “Yes,” she said, “we do have such a course but unfortunately with the education you have had, you just wouldn’t qualify for it. You wouldn’t be able to apply,” which was a big disappointment but as I turned to go, she stopped me. “Hang on a minute,” she said, “you see that guy over there, that man over there, the one in the brown jacket, he’s one of the photography lecturers here. Why don’t you go and speak to him.” And when I turned to look there was John Turner in the old brown corduroy jacket he always wore. At the time he was a new recruit to the photography department who had come to work alongside the very experienced photo-journalist, Tom Hutchins. Anyway, I introduced myself and John said, “I’m really busy but I can stop for five minutes.” And I think it was about two-and-a-half hours later when we finished talking.

Turned out that John, having only recently moved to Auckland, had bought himself a house in Mount Eden, right around the corner from where I was living at the time. And because his car happened to be in the garage that day, I gave him a lift home. I couldn’t attend the university but about a week later I started building a darkroom for John in his new house and in return he gave me private lessons. He taught me the basics, let me use his darkroom once it was built and most important of all, he allowed me the use of his own private collection of photography books—a really extensive library he had built up over the years. Books that were simply unobtainable in New Zealand at that time. Now we see them everywhere, but not then, you didn’t see them at all.

TV: What about your involvement with PhotoForum?

GB: I was involved at the very early stages, the first meetings and so on but I wouldn’t say to a great extent. I helped from time to time doing the page layout on the magazine, that sort of thing, which I have to say at the time I thought of as a fairly boring job. Anyway, I can remember attending meetings for PhotoForum—people like Peter Peryer, and John Fields. Simon Buis, who lived up the road from John, various people involved in the photography and also the art scene in Auckland in those days. It was interesting going to Australia at different times after that and meeting people like my good mate Phil Quirk, who used to rave about PhotoForum and say that Australia had nothing to equal it . . .

TV: What constituted photography [and its ethos] as you saw it or as it was thought of in PhotoForum, if that’s the term to use for it?

GB: Well, obviously it was a different concept, a different understanding or purpose if you like, than the camera clubs of the time had, or most of the commercial or professional photographers. You know, we were looking—or in my case learning to look—at life in a totally different way. One had a commercial imperative, one a set of club rules. And the other was—particularly in those days when documentary was in its ascendance, in the ‘60s and ‘70s,—people trying to look seriously at life, our social values, our politics, our more intimate personal experiences, a lot of work made then—certainly my own—was an attempt to share or show an understanding of ourselves.

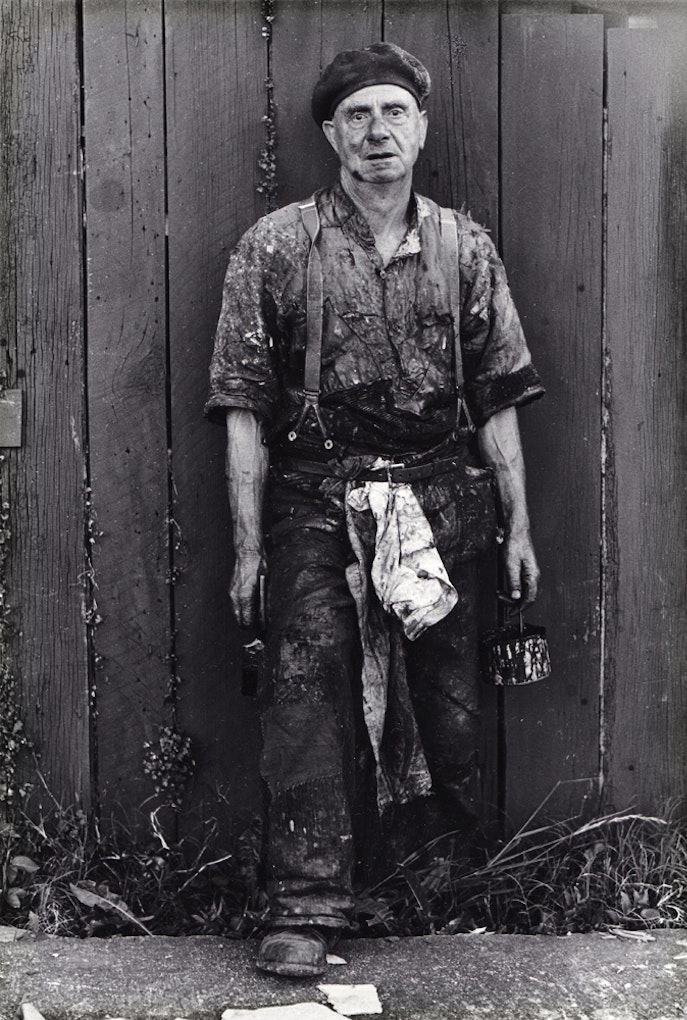

Glenn Busch

Man painting his fence

1973

GB: A little later on I started Snaps—A Photographers’ Gallery. There was quite a bit of interest in the first exhibition we had; TV stations arrived, the Auckland papers and so on, and the first question I was always asked was, “Why would anyone buy a photograph of someone they didn’t know?” I mean people were, in those days, perplexed by the idea that we had a photographic gallery that actually sold photographs. But, of course, in other places in the world this was nothing new, this had been happening for many years.

Although much early photography made in this country has been destroyed, made into glasshouses and so on, we do still have with us a tremendous amount of wonderful work made by those pioneering photographers. People who have made work that is of great value to us and whose names will be remembered. In the period of my own involvement, John Turner was the prime moving force for photography in New Zealand. During and since that time there have been numerous other people who have done marvelous things. You know, you think of Luit Bieringa and the National Gallery, of his great and continuing interest in New Zealand photography and what he has done to promote it. You think of people like Peter Ireland, who is one of our very best curators, writers and critics on photography. He was incidentally, also the best customer I ever had at Snaps. Peter would always come after the openings and look extremely carefully at the work. I never saw anyone else look as carefully as Peter did. A serious connoisseur of photography he would almost invariably put a deposit on something and pay it off, over a period of time. A patron of photography and the arts, in so many ways.

But going back to John Turner, in my experience, when something special happens, there is usually just one or two people who actually make it happen. That’s to say, there is usually a person, without whom, it would not have happened. And PhotoForum—along with many other things that have happened in New Zealand photography—would not have happened without John. It’s always easy to criticise people who do things—and constructive critique is a good thing—but yeah, there are people who do things and there are a lot of people who talk about doing things. Personally I owe a great deal to John Turner.

TV: Can you comment about how that core group of people, the associated group of people that constituted PhotoForum perhaps, were interested in advancing the photographic culture within New Zealand? Was it their motivation to give it the same sort of standing as in places like France or New York, where photography was definitely elevated to a fine art medium, people wanted to buy it, people wanted to have pictures of people on their walls?

GB: One of the other things that PhotoForum did, apart from the magazine, was to run workshops and those workshops were responsible for a whole lot of new practitioners coming onto the scene. I mean if you think of that wave of New Zealand photography that started with say, people like, well, Ans Westra, and then Richard Collins, Gary Baigent, and John Fields—that first exhibition of their work that John Turner curated at the Auckland City Art Gallery. I would think of them as the first group from around that period and then followed a number of others including myself, people who came out of those early PhotoForum workshops or came together in some way because of the things happening around PhotoForum. Obviously it wasn’t the only thing happening at that time, but it was the most important.

Apart from my own work, probably the biggest involvement I had at the time, was to start Snaps Gallery. That happened one time after I came back from working in a mine in Western Australia. I had a bit of money saved and after a quick look around found a space within a couple of days, in Airedale Street. The building at the time was I believe, the second oldest building still standing in Auckland. It was just like a couple of little terrace houses joined together really. And it was leased by a guy called Dave, who was a film editor. He, probably illegally, sublet half of it to me.

I went in and I was helped at the time by a couple of people, most notably Alan Leatherby, an old friend and photographer himself. We went into this little building that had a shower and toilet out the back and the first thing we did was make a couple of darkrooms. To accommodate the darkrooms we shifted the staircase, again illegally, and apparently dangerously, according to a number of architects who used to come and look at our shows We did this as cheaply as possible: wood and wiring was liberated from various places around the city, derelict buildings and so on. We had a mate who helped us wire up the place. All very unsafe by today’s standards, I’m sure, but it seemed to work at the time. And upstairs there was also a little room that I slept in.

The first exhibition we had was Max Oettli, a Swiss photographer, who used to work at Elam. Max was leaving the country, and we decided we’d copy what some of the potters were doing at the time and have a weekend sale of his work. We put up all this work and it was a great success. The party went on all weekend and then people just kept coming. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, so we just kept the door open and in fact we never closed after that. We started having exhibitions of around a fortnight’s duration. We used to have fairly famous little openings there that were attended by a lot of people. The place was so small that people flowed out onto the footpath and then the street. There was lots of music and lots of dancing. The architects, as I say, were very worried about the upper floor. When people were dancing it would vibrate, bounce up and down like crazy, and they were very afraid the floor was going to fall on top of all the people who were packed down underneath—it was a big party really, every couple of weeks we’d have a big party there.

TV: Being an exhibition space and having all these people that were involved in that community . . . I imagine in New Zealand at that time, other than a few select prints that might have travelled or were in the National Collection, it would have been photography seen in magazines and books like Illustrated Press, and the Life magazine type thing and Camera. How did that community of people start thinking about photography or photographs as objects and objects in their own right?

GB: It’s interesting isn’t it, one person does one thing, like John forging ahead with PhotoForum and out of it have come so many other things. His efforts with the major galleries and them starting to collect contemporary photography, the starting of Snaps, the burgeoning amount of new work being made and seen, all that and so many other things would not have happened at that time if it hadn’t been for John and his efforts. I guess it’s how the world grows, isn’t it? One person starts something and it starts to grow. If it has substance and quality and people feel it to be worthwhile, then it will spread. You can’t stop it. John’s efforts have had a major effect on what we think of as New Zealand photography today.

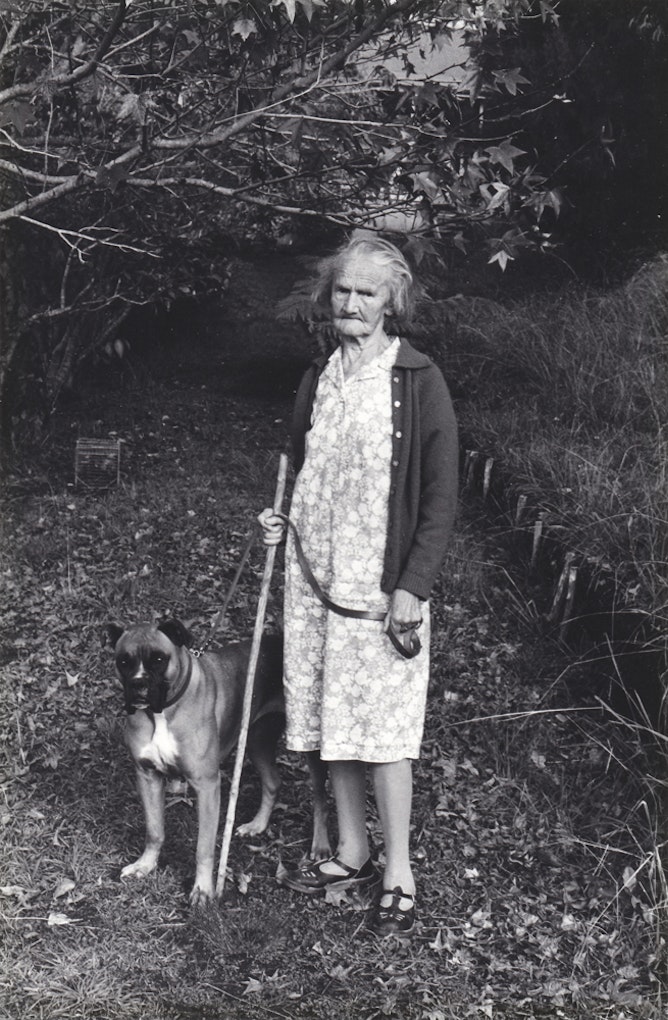

Glenn Busch

Woman with her dog

1973

TV: I’m really interested in how that community of people kept each other in check, how people thought about ethics and about that idea of representation, subjective truth and all that. PhotoForum, I guess, and the group of people around it would have contributed to that sort of education I guess?

GB: Yeah, they did, but I think actually, I think the opposite is true. I think ethics—apart from people’s personal ethics—ethics in the larger sense, were not thought about anywhere as much as they are today. We lived in less politically correct times. I know for myself, I used to think that making the picture was enough. I’m not sure that I do anymore. I used to think that a photograph was capable of doing a lot more than perhaps it does. My own interest has always been in people. And I guess that’s one of the reasons why I started writing down the things that people told me, the stories that they told me. In a way, a photograph is like a little short story, one that the viewer may need to supply the beginning and the end to. Perhaps that’s why I always liked to talk to people. It’s something that I often did. I was never particularly interested in, say, the Cartier-Bresson style of photography, where people would not even know they were being photographed. I mean I appreciate what he does, I think it’s beautiful work, it just wasn’t something I was interested in doing myself. I was much more interested in meeting people, making their image and listening to their story.

TV: Why do you think that the people, well, not all practitioners, but these days there’s a general sense in curatorial circles, that they don’t have quite that same enthusiasm for photography, in the way that PhotoForum originally was conceiving of it, I’m thinking now of The Active Eye and other such things? It still seems photography is underrepresented in major collections and in the exhibitions circuit.

GB: Yes, well I suppose there’s always been that sort of separation between photography and the other arts in New Zealand and around the world. What PhotoForum and other such groups and individuals have done is to have helped make people more conscious of photography as fine art, and also the importance to us of photographs in documentary work.

Speaking personally, I have never been particularly interested in that argument, to me, photography is photography. I’m not so interested in it being some sort of precious fine art object. I mean paintings are one offs, photography is not. And much of the modern gallery experience is a marketing exercise. I’m much, much, more interested in what the making of the photographs can do—the work of Lewis Hine for instance in the early 1900s, the purpose of its making in say Bruce Connew’s work in South Africa—than I am in having, you know, work honored in some gallery as a piece of fine art.

TV: What do you feel you have learnt from those early days of interacting with key people like John Turner, Peter Ireland and Luit Bieringa.

GB: I learnt about how enthusiastic people were about photography, how much they cared about it and treated it with respect. I learnt about what photography was capable of. I learnt from all those things, but I guess I knew from the time I saw the Brassaï show that it was something that is, or can be, very affecting. Much the same as any other work of art, like great literature for instance, great photography has the capacity to move people. Seeing those Brassaï photographs certainly moved me. Between then and now I’ve been privileged to see many special photographs that have continued to move me. And that hasn’t stopped or lessened in any way, I am still today looking at photographs that affect me.

TV: Any last words?

GB: Naw—too many words already, I doubt anyone is going to read this far. Let’s go and have a beer.